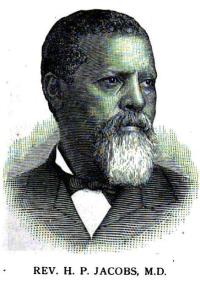

Ypsilanti’s large and historic African-American community, which dates to before the Civil War, has given much to the region and to the country. Elijah McCoy’s achievements have rightly been praised by his home town, and he is easily the most famous African-American from the city. However, there was another man living here around the same time that had an impact felt across the country, and perhaps the one of the most historically important persons to ever call Ypsilanti home.

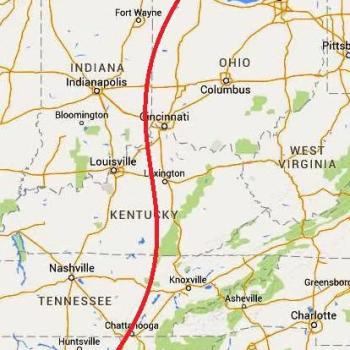

Henry P Jacobs was born Samuel Hawkins on July 8, 1825, and with the rest of his family was held in bondage by the wealthy planter Dill family near Ashville, Alabama. His family had moved with the Dills from South Carolina to St. Clair County, Alabama when he was a child. Settling near the Coosa River in the foothills of the Appalachians, the Dills would own over thirty human beings, making them among the wealthiest of their class in the county.

Approximate Site of Dill Plantation, Ashville, Alabama.

The young Samuel was said to be too small to work in the fields and was charged with aiding an elderly, and invalid, member of the family. It was from this man that Samuel learned how to read and write while enslaved. That education would have a profound impact, both personally and the impact he would make on the world around him.

By around thirty years of age, Samuel had married a woman named Louisa and had a number of small children. He must have planned his escape meticulously, perhaps thinking about it for years. He forged ‘free papers’ for his wife, their three children and two of his brothers, took his masters horse and buggy and stole for Canada on July 24th, 1856. Twice they were stopped and their papers examined, but they arrived safely on the Detroit River on August 19th of that year, just over three weeks and 750 miles later.

On the 20th of October 1856 Hawkins shed his slave name and took the name, along with his brothers, of Jacobs. Henry P, later known almost exclusively as H P Jacobs was baptized in the Detroit River by the Reverend William Troy. Troy was minister to Canada’s refugees and author of Hair-breadth Escapes from Slavery to Freedom, who, like Jacobs, had escaped from bondage and also like Jacobs, would return South after the war.

On the 20th of October 1856 Hawkins shed his slave name and took the name, along with his brothers, of Jacobs. Henry P, later known almost exclusively as H P Jacobs was baptized in the Detroit River by the Reverend William Troy. Troy was minister to Canada’s refugees and author of Hair-breadth Escapes from Slavery to Freedom, who, like Jacobs, had escaped from bondage and also like Jacobs, would return South after the war.

Thousands of people had found refuge in Canada, many escaping from slavery and others escaping from racism in the North, in the years before the Civil War. Many of them would later settle in Ypsilanti and other town in the environs of the Detroit River. A strong relationship between Michigan and communities of color in Canada is evident in many of the stories and documents from this time. It is possible that the Jacobs family travelled through Ypsilanti on their way to Canada. It is there where we next find the family living with the black barber Norris Arnold in the years prior to the Civil War.

Jacobs found work here as a janitor at the Michigan Normal School, now Eastern Michigan University. This would prove to be a fortuitous decision in the lives of his daughters and granddaughter. Jacobs would enroll his daughters in the Music School attached to the college. They would go on to become accomplished musicians and teachers themselves. The hostility some felt for Jacobs in Ypsilanti is evidenced by newspapers blaming him, because of his race, for an 1859 fire at the school.

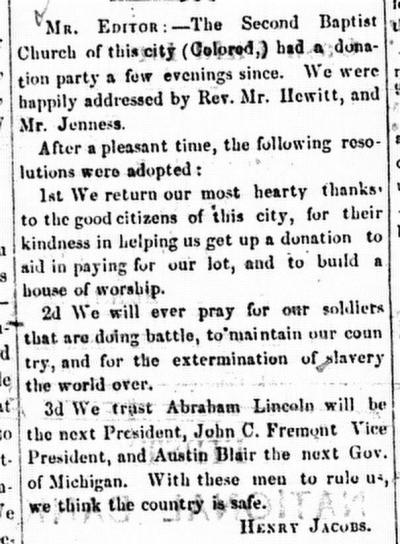

Jacobs was ordained a Baptist preacher on September 18, 1858 and quickly became a leader of Ypsilanti’s black community. Within a few years he had help to found and was first pastor of Ypsilanti’s historic Second Baptist Church. The congregation of the Second Baptist Church met at several locations in the town including the Presbyterian Church on Pearson Street, a private home on Babbit, the Adams Street School and in a building on Michigan Avenue between Normal and Ballard Streets.

A January 11, 1865 Ypsilanti Free Democrat writes this about the Church then:

‘Rev. Mr. Jacobs, for a number of years a janitor at the Normal, is pastor. He is a good a thorough worker, and of good natural abilities. The Church have entered the house [the old Presbyterian Church] under very promising auspices. There is debt resting upon the purchase. They look to the benevolent in our city and elsewhere to aid them. There is also a ladies aid society, whose object is to take care of the sick and bury the stranger dead. It meets once a week for moral improvement. Rev. H. Jacobs is president of the society.’

Old Second Baptist, Catherine and Hamilton.

Said not to “stoop to the whims and petty prejudices in order to gain popularity”, H P Jacobs would become one of the most prominent black Baptist ministers in the country in the years that followed the Civil War.

April 17, 1863. The Liberator.

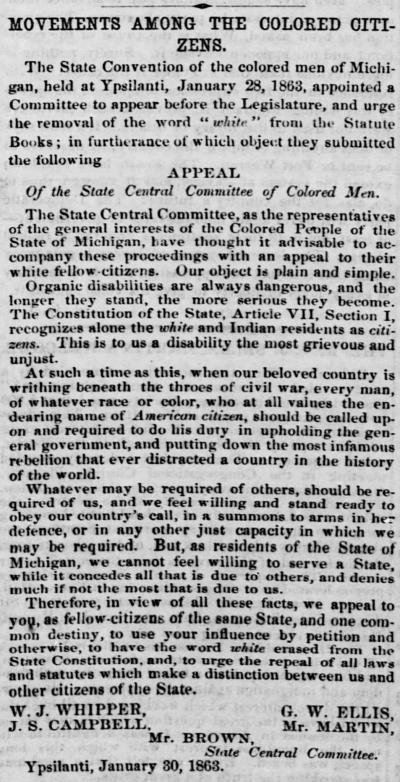

H P Jacobs was among the hosts of an historic 1863 meeting of Michigan’s African-American men in Ypsilanti, which included leading black figures of the day, like “The Father of Black Nationalism”, Martin R. Delany. The meeting declared Michigan’s black men more than willing and ready to fight in the Civil War, but demanded first that the State treat them as equal citizens, remove the word “white” from all statues and revoke any laws “that make a distinction between us and other citizens of the state.” This historic appeal for civil rights came even before black people were considered citizens of the country and one hundred years before Martin Luther King led the March on Washington in the summer of 1963.

HP Jacobs Letter to Ypsilanti Commercial. April, 1865.

Jacobs also founded a school for African-American children in Ypsilanti. Originally, black youth could go to Ypsilanti schools but were required to sit in the back. Tired of this daily humiliation, Jacobs led black families in removing their children from school and demanding black teachers under conditions where their children would be treated with respect. The first teacher would be a black cooper and the school would also host Michigan’s first black school principal.

The Liberator. August, 1864.

Thus began the many years of completely segregated schooling in Ypsilanti. For many years this school was on South Adams Street and would be both a source of pride and anger on the City’s south side. The school would become the battleground for an early NAACP legal challenge segregation during World War One, a story widely talked about among African-American nationally and reported on in W.E.B DuBois’ Crisis magazine.

Ypsilanti’s segregated Adams Street School. 1900s.

It seems wherever Jacobs went, he built a school. Immediately after the Civil War he returned south with his family where he helped to establish a seminary and day and night school to teach those newly freed from their shackles to read and write in Natchez, Mississippi. The school which Jacobs founded and where he and his family taught is now known as Jackson State University, one of the most historic and respected places of higher learning for African-Americans in the country. Within ten years, Jacobs had gone from being enslaved to a Janitor here at the Normal to the founder of the Natchez Seminary, and his activity had barely begun.

The Natchez Seminary

His eldest daughters, just in their early teens also taught with him. His connections to his children, Anna, Samuel (who died in Ypsilanti in the 1870s), Mary, Elizabeth and Julia, would remain strong. As an illustration: at least two of his daughters, Anna and Mary would be continue to use their maiden name Jacobs in their last names after marriage, almost unique for the time. Another factor keeping the family close was the early death of Anna’s mother, Louisa in Natchez. As a result, Anna would take in her younger siblings and raise them as the, now young women, returned to Ypsilanti.

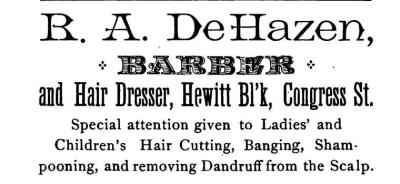

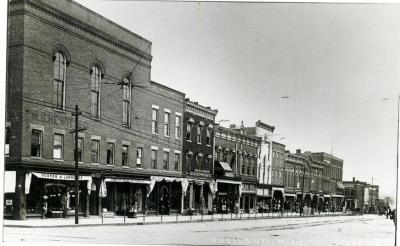

Jacobs’ eldest daughter Anna married Ypsilanti African-American barber Robert De Hazen, who had a shop at the Follett House in Depot Town and then moved to the second floor corner of Hewitt Hall, where the Mix now is, for decades. The building once had a third floor containing a hall that hosted many events of importance to Ypsi’s black community, including multiple speeches by the great African-American freedom fighter and orator Frederick Douglass. DeHazen, or ‘Al’ as he was known, was a leading member of Ypsilanti’s vibrant African-American community and by all accounts a rather dapper man.

Hewitt Hall (now The Mix) DeHazen’s shop is the 2nd floor corner window.

As a barber and business owner, DeHazen’s work made him often a mediator between the white and black community, even after barbering became entirely segregated, Al would hold the respect of many white Ypsilantians. Al hosted masquerade and holiday balls for the black community and was a leading member of many Africa-American fraternal organizations. His parlor also, most probably, contained a room for men to drink and play games of chance away from prying eyes.

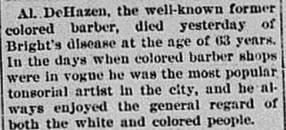

Al DeHazen’s 1901 Ypsilanti death notice.

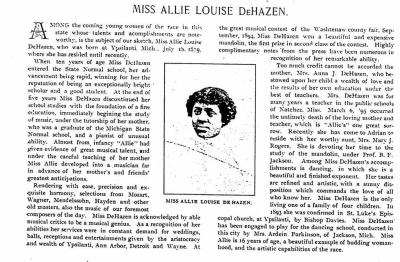

The house of Robert DeHazen and Anna Jacobs-DeHazen, which still stands on South Adams, was the African-American household closest to Ypsilanti’s downtown, and the dividing line between black and white Ypsilanti. Al DeHazen house, quite literally, stood where he stood in the city socially. This home is still standing and would have seen many visits of H P as he returned to visit his family, preach or engage in political activity. Living there occasionally were also Anna’s sisters Julia and Mary, and the De Hazen’s only surviving child, Allie. After Anna died in 1895, Robert married Amanda Roper in 1897, a young music student of his wife’s. Al died in 1901. Their daughter, HP Jacobs’ granddaughter, Allie, would live to old age, the wife of a doctor and music teacher herself in Washington, Pennsylvania.

Article on Ypsilanti’s Allie DeHazen, HP Jacobs’ granddaughter.

Henry P. Jacobs became one of the most important men in Mississippi in the Reconstruction years. In addition to helping found what would become Jackson State University he was elected to the Constitutional Convention that drafted Mississippi’s post-war Constitution and then elected to the State’s senate three times in short order as well as serving on the Natchez City Council. He led one of two powerful Reconstruction-era factions of black politics; the other led by John R. Lynch, in Mississippi and became a leading black voice in Southern politics.

As African-Americans emerged from bondage, they founded hundreds of churches and societies; they married freely and planned futures for the first time. A whole black world was being created out of the ashes slavery and the war in those years and H P was at the center of that creation. He organized beneficent societies and freedman to pool their money and purchase the plantations they formerly labored on as worker-owners. H P launched dozens of such plans, some coming to fruition, others not, in the heady days when Reconstruction made such things possible.

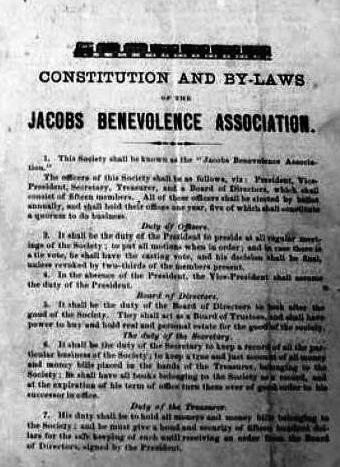

Mississippi’s Jacobs Benevolence Society. Founded by HP Jacobs in the 1870s.

He served as President of the Missionary Baptist Convention of Mississippi for seven years. In essence he is the founder of every black Baptist church in Mississippi and was constantly travelling around the state setting up congregations as part of his work. According to a brief biography written during his lifetime in 1892’s Our Baptist Ministers, H P Jacobs was “a man of great will power and determination. He believes it is never too late to do good and is constantly using his efforts for the good of his people.”

July 23, 1886. Ypsilanti Press.

He kept in close contact with his friends and relatives in Ypsilanti; local newspapers printed his inaugural speech to the Mississippi senate and in later years he would travel to Michigan to speak at the Emancipation Day Celebrations or other events. Indeed, Jacobs is easily the most mentioned local Black man in the local press of the 19th century, and yet remains almost entirely unknown today. Much of the organization of Emancipation Day events (held August 1st in honor of the 1834 end of slavery in the British Empire – and the possibility of freedom in Canada) fell to the Colored Knight of Pythias, a black fraternal organization. As a junior Grand Master of his local lodge, Robert De Hazen, Jacobs’s son-in-law, took a leading part in preparations for what was the grandest social and political occasion of the black calendar.

Ypsilanti Commercial. August, 1876.

Breaking with the Baptist Convention in later years, Jacobs would continue to grow and learn. He studied medicine though no school would take him and practiced in various black communities for years before, at the age of 65, he was given his doctorate in medicine from a college in Louisville, Kentucky. As a physician, in what was then his old age, he travelled to the newly forming black communities of Kansas and Oklahoma to serve as doctor, healer, educator, pastor, and leader.

This remarkable man and his family, from slave to janitor to state senator in ten years, were able to achieve what they achieved because of the climate that that rose from the Civil War in the period of Reconstruction. Those same advances would be closed down in just a few short years as a counter-revolution of Jim Crow swept aside the gains paid for by blood in the Civil War. It must have been terrible for Jacobs to see and live through this defeat. We do know that he continued to strive to the ends of his days, sometime in the early 1900s, “for the good of his people”, though.

Institutions founded by Jacobs still dot the landscape, from our own Second Baptist to Jackson State. However, his legacy remains largely forgotten, a casualty of the defeats suffered in the years of Jim Crow and since It is well past time for us to retrieve the memory and legacy of H P Jacobs and his family. This man who travelled the country, and yet constantly returned to his home in Ypsilanti, helped to remake America after the Civil War and lived a life of inspiring service. His memory is a challenge to us to live up to the ideals which sought a “second birth of freedom” for the country 150 years ago this year. How many others who work in drudgery, who clean the floors of our schools, could be leading them instead? That is the challenge of HP Jacobs. We can begin rising to that challenge by remembering him.

—

As part of the Ypsilanti African-American Mural Project, local high school students completed a mural in honor of HP Jacobs on the side of historic Currie’s Barbershop at 432 Harriet Street. To learn more and keep up on progress with the mural project on Facebook.